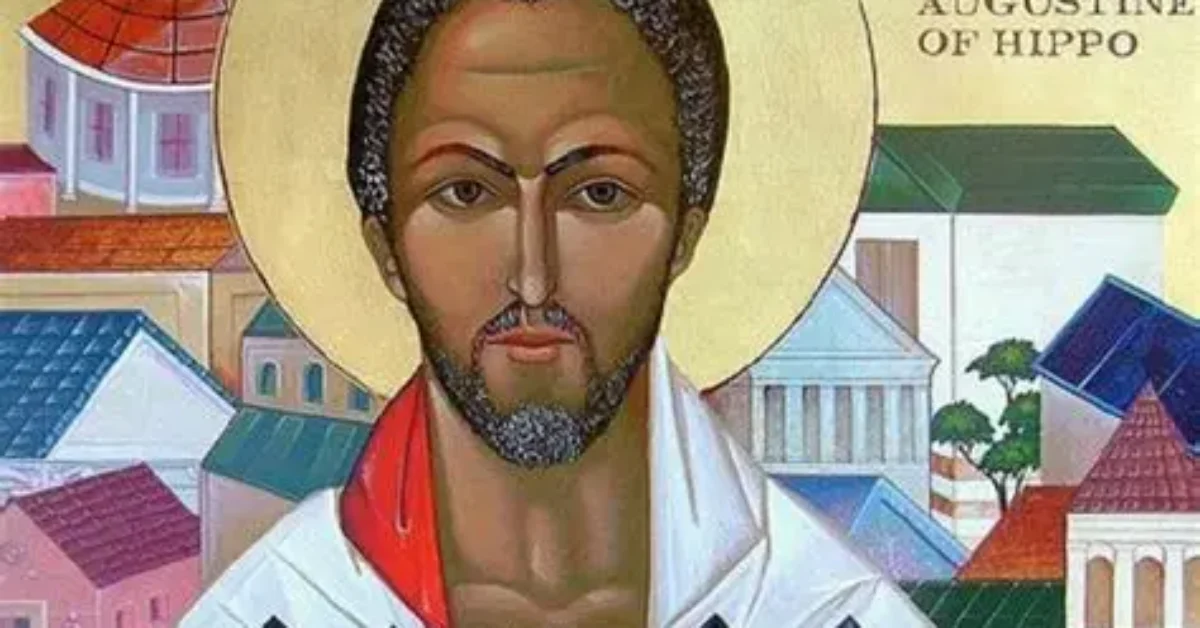

I (Kent) am preparing to teach a graduate level course entitled, “Baptism and Conversion.” Central to the course’s deliberation is the process of conversion facilitated by the catechumenate, both ancient and modern. As a lens into the ancient process, we are reading Willaim Harmless, S.J., classic research into the catechumenate of Augustine in Hippo, Augustine and the Catechumenate (The Liturgical Press, 1995). Augustine (and Harmless) still have much to say to us in the 21st Century as we seek to discern a catechumenal plan that is welcoming, formative, and spiritually persuasive. So I am going to let Augustine speak over the next two weeks, gleaning from him stalks of wisdom to feed our catechetical hunger.

As Harmless notes, his work is a case study:

“It will explore in detail what Augustine did with his baptismal candidates, what he said to them, and what his reflections on the experience were. And the approach will be to read the texts with an educator’s eye: to chart the course and rhythms of his catechesis; to note what issues he thought important, what language he used, what feelings he roused, what actions he called for; in other words, to discern how he envisioned conversion and how he nurtured it” (Harmless, 29). Language, action, feelings…definitely all parts of the conversion to the Triune God of the entire human creature. All of that experienced in the catechumenate process. And all of it bringing to reality for the catechumen: belonging, believing and behaving.

We neglect how people feel as part of conversion to our own great peril (and hinder the work of the Spirit in the process). As Rev. Dr. Scott Bruzek says (my paraphrase), “We used to ask people what they thought. Now we ask them what they are feeling.” That’s not meant to disparage what people think. But they go together and in the majority of cases in this current world what people are feeling is THE access point into building a relationship.

Augustine certainly didn’t ignore feelings. Of his own baptism in his Confessions he says:

“We were baptized, and all anxiety over the past melted away for us. The days were all too short, for I was lost in wonder and joy meditating upon your far-reaching providence for the salvation of the human race. The tears flowed from me when I heard your hymns and canticles, for the sweet singing of your Church moved me deeply. The music surged in my ears, truth seeped into my heart, and my feelings of devotion overflowed, so that the tears streamed down. But they were tears of gladness” (Confessions, translated by R.S. Pine-Coffin, New York: Penguin Books, 1961; cited in Harmless, 98).

This is the effect of the Word embedded in catechumenal sacrament and ritual. The Holy Spirit waters the emotions toward streaming tears of gladness. Augustine’s baptismal, emotional stream reflects what Ambrose taught him:

“You are inebriated in spirit . . . . for the one who is inebriated with wine totters and sways; the one who is inebriated with the Holy Spirit is rooted in Christ. And so, glorious is the inebriation which affects sobriety of mind” (Yarnold, The Awe-Inspiring Rites of Initiation, London: SPCK; cited in Harmless, 103).

When did anyone ever say to you that the goal of the catechumenate and of baptism is inebriation. Well, it is. Inebriation in Christ. Thus Augustine experienced his conversion. And so, we pray, might all of the church’s catechumens.